As many of you may be aware, on March 25, the whole country will be recognizing National Medal of Honor Day. In a show of respect for the occasion, we’re highlighting the medal’s first recipients.

On April 12, 1862, Union raiders all participated in one of the most daring operations of the entire Civil War, called “Andrews’ Raid”. It is perhaps better known as “The Great Locomotive Chase.”

Contextualizing Andrews’ Raid

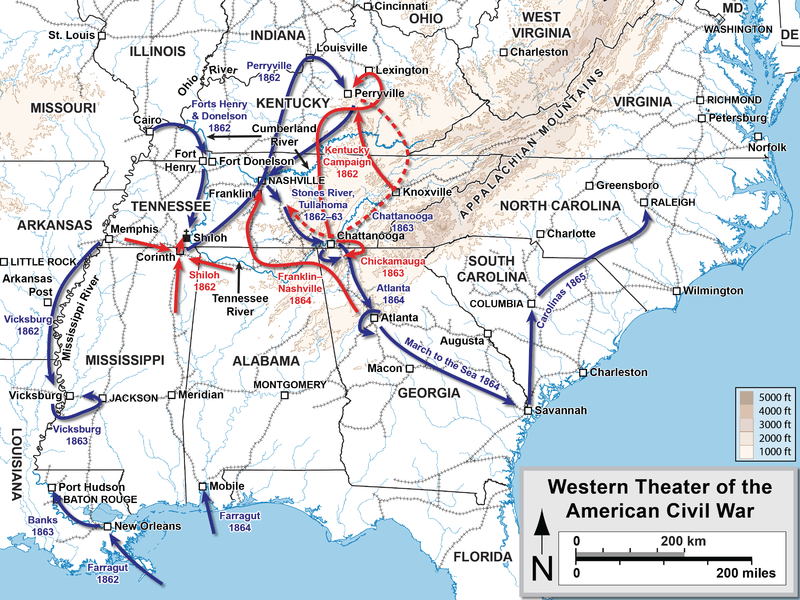

When talking about Civil War history, a lot of the attention gets placed on the Eastern front. With the Union’s and Confederates’ capitals both residing within two hours of each other (Washington, D.C. and Richmond, respectively), it makes sense that large importance was placed on the East. However, what was happening in the West was just as vital. By spreading the war out, the Confederacy would have a hard time defending the vast amounts of territory, especially with their relatively smaller force. Toward the end of the war, the Western theater would see major victories in Vicksburg, Chattanooga, and Atlanta, which served as near insurmountable losses to the South.

Map by Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com

If we rewind back to the start of the war, the Union was suffering from a lack of clear command in the Western theater. The departments of Kansas, Missouri, and Ohio could not agree on a plan for attacking the territory. In fact, the only general who seemed to get much done at all was a brigadier general by the name of Ulysses S. Grant. In February of 1862, Grant would lead his army to victories at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, which left Tennessee open for invasion. Soon after, Nashville was captured by Brig. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, who was head of the Department of Ohio’s army.

Introducing Andrews

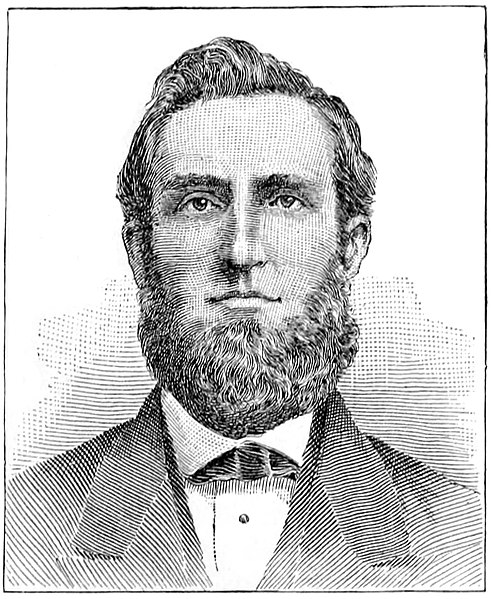

Shortly after, Buell’s army was merged into the new Department of the Mississippi and Buell was ordered to go southwest with Grant’s army. What was left in Nashville was a 7,000-man garrison that formed with Maj. Gen. Ormsby Mitchel’s 10,000-man division. But before he left, he was approached by a civilian spy and scout named James J. Andrews. Andrews proposed allowing him and eight men to steal a train in order to wreak havoc in Georgia. Buell signed off on the plan; however, it had to be canceled upon their arrival in Marietta.

Andrews still wanted to follow through on the idea but would need more men, as the original group of raiders decided they had no interest in being undercover behind enemy lines. Andrews would soon get his opportunity at a do-over.

Pictured above is James J. Andrews

The Plan Comes Together

In Nashville, Maj. Gen. Mitchel was seeking a way to capture the city of Chattanooga. Chattanooga was an important railroad and river junction for the Confederacy, so capturing it would be a major success for the Union. However, Mitchel knew that the region’s geographical factors and the South’s ability to send reinforcements there would make taking it an incredibly difficult task. However, if they could somehow disrupt the Atlantic and Western Railroads that led into the city, they might have a shot. This was exactly what James Andrews proposed to Mitchel.

Andrews would gather a larger group of men this time, increasing his raiders from eight to twenty-two men, including another civilian named William Hunter Campbell. The plan involved stealing a train near Big Shanty, a stop just north of Atlanta, and taking the train north toward Chattanooga while causing as much destruction to the railroad infrastructure as possible. Big Shanty was chosen as the launching point as it lacked a telegram, theoretically giving the raiders more time to complete the mission.

The Calm Before The Storm

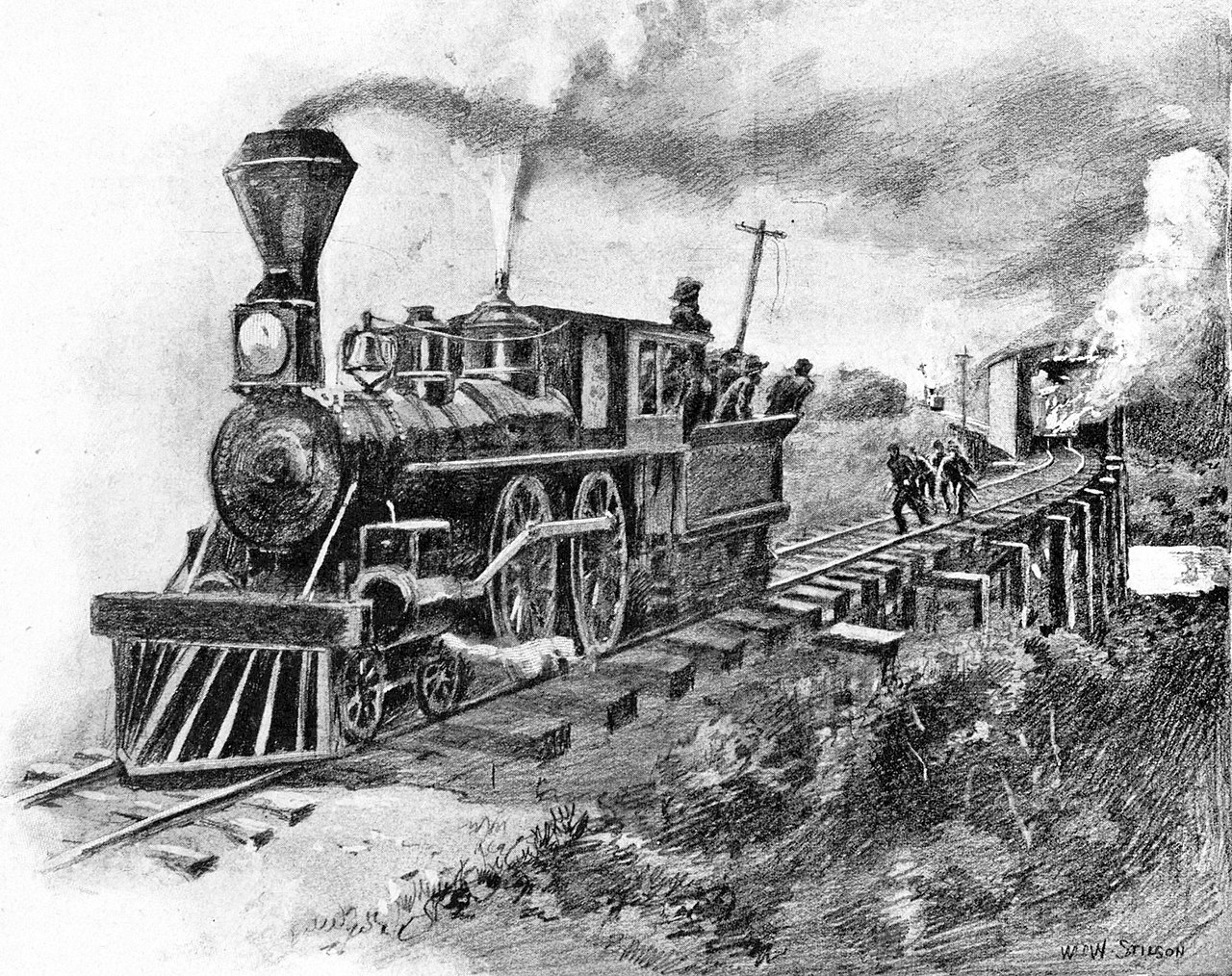

Come April 12, the day of the raid, two men had already missed the rendezvous point. When the train, The General, made its stop at Big Shanty, the remaining men proceeded with the plan. They stole The General, its three passenger cars, and a crowbar as they made their way north.

There was one problem, however. As they were leaving, the train’s conductor spotted The General chugging away from Big Shanty. The conductor, William A. Fuller, and two other men proceeded to sprint after the train, eventually finding a handcar to continue the chase. While it seems improbable that Fuller could catch the raiders, it is important to note that trains in those days averaged a speed of only 15 mph. And along with their making stops for sabotage, it was a very real possibility they would be caught. The chase was now on.

The Chase Begins

Not long after leaving Big Shanty, Andrews and his crew ran across a small locomotive named Yonah. Andrews considered destroying the train; however, he deemed that the time it would take to complete such a task would be counterproductive. This would prove to be a mistake as Yonah would soon be commandeered by his pursuers.

Nevertheless, the raiders continued up north, encountering a number of obstacles and holdups. The sky also opened up, and the rain began to soak their stockpile of wood. Soaked wood meant less fuel. And when traversing the hills of northern Georgia and southeastern Tennessee, fuel was a precious commodity.

In addition, it became apparent that the process of destroying the track behind them was taking too long. Fuller, who now had eleven Confederate soldiers with him, was gaining ground on the raiders. Finally, just 18 miles off from Chattanooga, The General ran out of fuel. With no choices left, Andrews and his men ran off, abandoning the train and ending the chase.

The Fallout

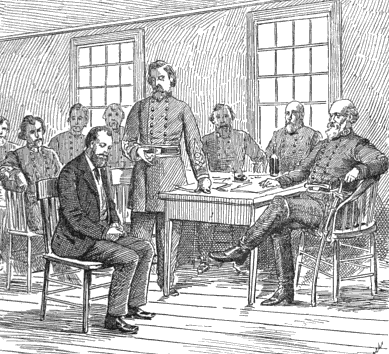

Unfortunately for the Union, Andrews and his raiders were all captured within two weeks. The bold plan did not pay off. While Maj. Gen. Mitchel was able to capture Huntsville, they were not able to attack Chattanooga at that time. Furthermore, upon capture, eight of the twenty-two raiders were found guilty of “acts of unlawful belligerency” and were promptly executed, including Andrews himself.

When word of the daring plan reached the North, the men were hailed as heroes. Luckily for the other fourteen men, they either escaped to safety or were released in a prisoner exchange that occurred on March 17, 1863. A few days later, after having their story corroborated, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton would present six of the raiders with the recently approved Medal of Honor. Among them were Private Jacob Parrott (who was the very first recipient), Sergeant Elihu H. Mason, Corporal William Pittenger, Corporal William H. H. Reddick, Private William Bensinger, and Private Robert Buffum.

Eventually, nineteen of the raiders were presented with the Medal of Honor as well. Both Andrews and the other civilian, William Hunter Campbell, were not eligible to receive the commendation. Of those recipients, their citations read, “One of 19 of 24 men (including two civilians) who, by direction of Gen. Ormsby M. Mitchell, penetrated nearly 200 miles south into enemy territory and captured a railroad train at Big Shanty, Ga., in an attempt to destroy the bridges and track between Chattanooga and Atlanta.”

The Legacy of The Great Locomotive Chase

Today, there are multiple markers dedicated to Andrews’ Raiders all throughout the area in which the chase took place. At the Chattanooga National Cemetery, a monument was erected in dedication to the raiders.

One daring raid that was a long shot, at best, started a tradition that has carried into the present day and surely will continue into the future—a tradition of heroism and valor that would come to represent one of the highest achievements one can receive in defense of their country.

They, of course, are only a few of the many brave individuals who have been awarded this commendation. To read more stories like this, you can click here to learn about two-time recipient Maj. Gen. Smedley Butler. To learn more about National Medal of Honor Day, please visit our article detailing its history here.